The North American housing crisis has reached a breaking point.

With home prices soaring beyond reach and rental costs consuming ever-larger portions of paychecks, communities are desperately seeking solutions. Yet when higher-density housing enters the conversation, misinformation and fear often drown out evidence-based discussion.

The words "density" or "upzoning" can trigger immediate neighborhood resistance based not on facts, but on deeply ingrained myths that have shaped our cities for decades. These misconceptions don't just stall progress—they actively contribute to sprawl, unaffordability, and exclusion. It's time to confront these persistent myths head-on and examine what the evidence actually tells us about density's impact on our communities and quality of life.

This does not mean that every place should be dense or walkable. While that might be my personal preference, it seems that Americans are split almost evenly between those who prefer walkable and amenity rich places compared to those who prefer driver-only suburbs and rural areas. The problem is, only about 3% - 5% of our land use patterns in the U.S. currently support walkable neighborhoods with levels of density that actually allow for choices in the market place.

Myth #1: Higher Density Housing Will Reduce Property Values of Nearby Homes

Perhaps the most persistent myth in discussions about urban development is that higher-density housing projects will cause neighboring property values to plummet. This concern frequently emerges during zoning debates and public hearings.

The Reality: Research consistently shows that well-designed higher-density housing typically has either a neutral or positive effect on surrounding property values.

A comprehensive 2021 study by the University of Utah's Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute found that single-family homes located within a half-mile of newly constructed apartment buildings experienced higher overall price appreciation than homes farther away—10% median value increase per year compared to 8.6% for more distant properties.

Homes closer to multifamily housing also had an 8.8% higher median value per square foot than those beyond a half-mile away, even though the houses tended to be slightly smaller, about seven years older on average, and had smaller lots.

Thoughtfully implemented density can actually enhance neighborhood desirability and property values by:

Creating vibrant street life and supporting local businesses

Enabling improved public transportation options

Funding infrastructure improvements through increased tax base

Supporting greater amenities and services within walking distance

When density is designed with consideration for neighborhood context, quality architecture, and appropriate transitions between housing types, it can become an asset rather than a detriment to existing communities.

Myth #2: Density Always Means High-Rise Apartment Buildings

When many people hear "density," they immediately picture towering high-rise apartments that dramatically alter neighborhood character. This misconception often drives opposition to any proposed density increases.

The Reality: Housing density exists on a spectrum and can be achieved through various housing types that maintain neighborhood scale. "Missing middle" housing—including duplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, courtyard apartments, and other small-scale multi-unit buildings—can significantly increase density while fitting into existing neighborhoods. These housing types historically existed in many American neighborhoods before being prohibited by exclusionary zoning.

A big thanks to Dan Parolek and his team at Opticos Design for coining the term Missing Middle and pairing it with hundreds of compelling images to remind us all that single-family homes are great for one segment of the population, but many other important and attractive options have been missing for far too long.

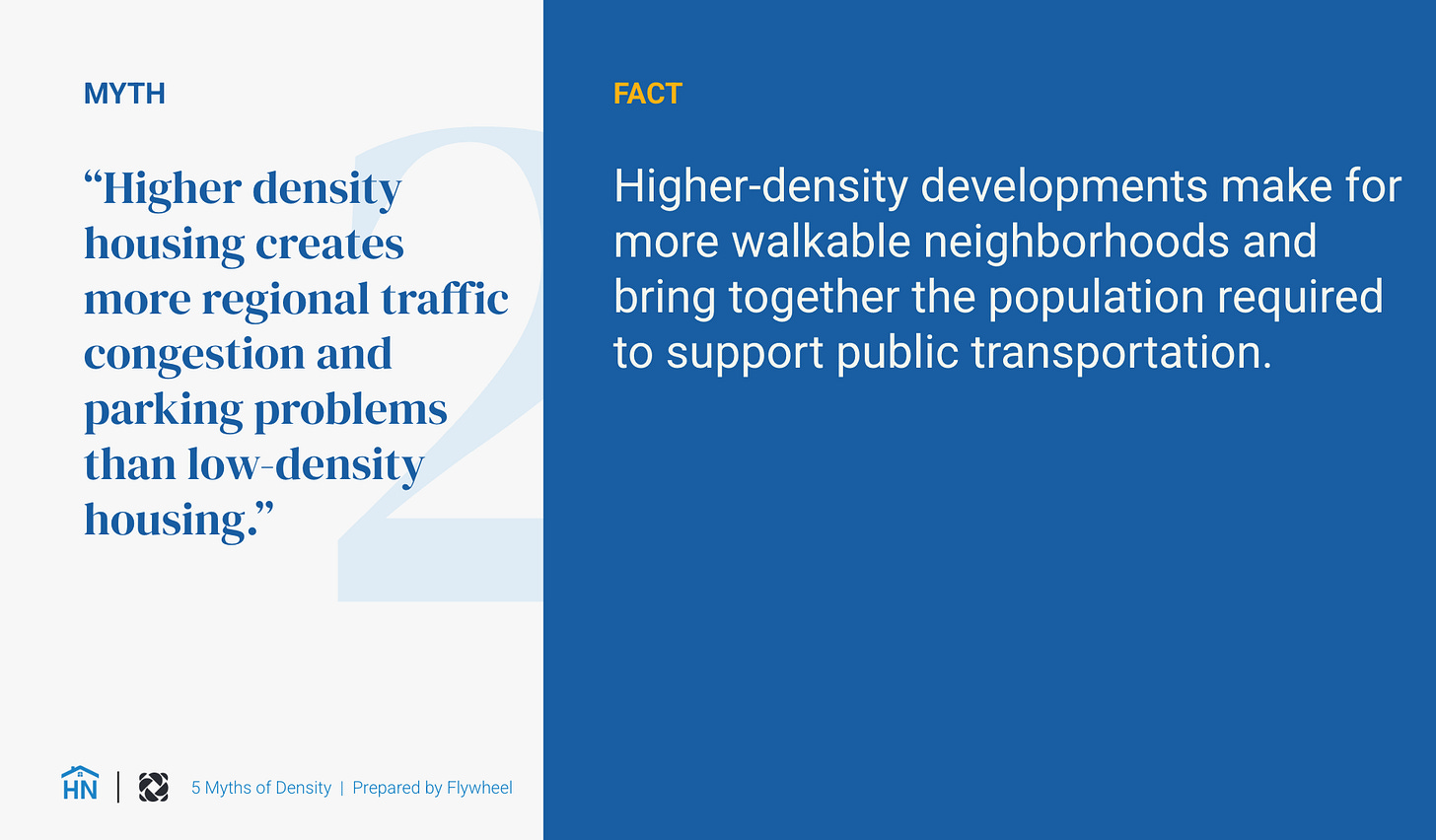

Myth #3: Higher Density Will Create Unsolvable Traffic Problems

A common concern about density is that more residents means more cars and therefore more traffic congestion.

The Reality: While poorly planned density can indeed create traffic challenges, thoughtfully designed dense neighborhoods can actually reduce car dependency. Higher densities make public transportation more viable and efficient. Dense, walkable neighborhoods enable residents to meet daily needs without driving, reducing overall vehicle trips. Studies show that residents in well-designed dense areas own fewer cars and drive less than their counterparts in sprawling suburbs.

A comprehensive study by the Arizona Department of Transportation found that higher-density, mixed-use developments designed to be walkable and accessible to regional transit could reduce residents' VMT by an average of 25 percent, with reductions ranging from 20 to 45 percent in some jurisdictions. The study also found that "roadway congestion along the corridors in the urban settings was found to be lower than that found in the control corridor" with low-density development.

Research has identified what planners call the "4 Ds" that reduce driving and congestion: Density, Diversity (mixed land uses), Design (walkable streets), and Destinations (access to jobs and amenities). A Massachusetts study found that increasing land use mix alone could reduce VMT by 4.3 percent, as "siting stores and other destinations within walking distance of where people live is one of the most powerful ways to reduce car traffic."

Higher densities support more efficient and diverse transportation systems, create environments where walking and cycling are practical options, and allow residents to meet daily needs without long car trips.

Density is not just an urban phenomenon. It can also work very well in suburban and small town contexts with other uses mixed in or very close by.

The data shows that well-designed density is part of the solution to traffic congestion, not its cause.

Myth #4: Denser Housing Attracts Crime

Some opponents of density suggest that multi-family housing brings increased crime to neighborhoods.

The Reality: Research consistently shows that there is no inherent correlation between housing density and crime rates.

A GIS-based study examining the relationship between crime rates and land-use patterns found that "high density and multi-family development are not necessarily associated with high crime rate, but socioeconomic status is." In fact, the researchers discovered that some areas with higher population densities had lower crime rates than lower-density neighborhoods in the same city.

A Scientific American report cited in Builder Magazine noted that "even when the researchers factored in the higher population of cities versus rural living, they found no significant correlation with higher crime rates." The study pointed to examples like the Netherlands, which has 13 times higher population density than the United States yet has an eight times lower homicide rate.

Recent research from UC Irvine's Livable Cities Lab specifically studied affordable housing developments, often a target of density-related crime concerns, and found that rather than increasing crime, these developments actually decreased crime rates in the surrounding neighborhoods.

What does influence crime rates? Socioeconomic factors such as concentrated and isolated poverty, unemployment, and low educational attainment are consistently stronger predictors of crime than housing type or density.

Well-designed density in neighborhoods that include a mix of both market-rate, middle-income, and affordable housing have been shown to dramatically increase opportunity for economic mobility (See “Moving to Opportunity, Raj Chetty) and enhance safety through "eyes on the street"—the natural surveillance that comes with more people present in public spaces.

Mixed-income neighborhoods with various housing types can build community resilience and social connections that actually improve safety outcomes.

Myth #5: Density Is Environmentally Harmful

Some argue that increasing density destroys green space and natural environments.

The Reality: Compact development is significantly more environmentally sustainable than sprawl.

Higher density development creates opportunity for all of the following:

Preserves undeveloped land elsewhere by accommodating growth in existing urban footprints

Reduces overall energy consumption through shared walls/heating/cooling

Decreases per capita carbon emissions through reduced car dependency

Enables more efficient delivery of services and infrastructure

Can incorporate green design elements including rooftop gardens, green spaces, and sustainable transportation

In fact, providing housing in existing urbanized areas is one of the most effective strategies for combating climate change.

Myth #6: Higher Density Overburdens Infrastructure and Public Services

A common argument against density is that it will overwhelm existing infrastructure—roads, water, sewer, schools, and other public services—leading to higher costs for all residents.

The Reality: Multiple studies show that infrastructure costs per capita actually decrease significantly with higher density.

A study published in the journal Sustainability found that "infrastructure costs per capita are the highest in low-density areas and the lowest in high-density areas." This is because the same length of water pipes, sewer lines, roads, and utility connections can serve more people in dense developments.

Research published in Urban Studies examined municipal spending across the United States and found that "density was inversely associated with per capita municipal expenditures" for numerous infrastructure categories. Put simply, as density increases, the cost to serve each resident decreases. The study found lower per-person costs for fire protection, streets and highways, parks and recreation, sewer, solid waste management, and water in higher-density areas.

In metropolitan Atlanta, despite adding 1.3 million residents, the region now withdraws 10% less water than in 2000 due to efficiency improvements, showing how existing infrastructure can accommodate growth without strain. Another analysis by Smart Growth America found that compact development reduces infrastructure costs by 10-30% compared to conventional sprawl.

With many U.S. cities facing massive infrastructure replacement costs in coming decades, strategically increasing density around existing infrastructure is actually a fiscal necessity. As a Smart Growth America researcher explains, "If you have a lot of people for a given length of road, then you are using that [road] more efficiently, so the average cost per capita should be lower."

Thoughtfully planned density doesn't overburden infrastructure—it helps communities use it more efficiently and sustainably.

Moving Forward

As communities address housing affordability challenges, it's crucial to engage in fact-based discussions about density. By moving beyond myths and examining evidence, we can design neighborhoods that are inclusive, sustainable, and enhance quality of life for residents of all income levels.

Thoughtful density isn't just about adding housing units—it's about creating vibrant, walkable communities where people can live, work, and connect with each other. When we approach density with careful planning and design considerations, we can create neighborhoods that offer both more housing options and higher quality of life for all residents.

If you’re a local decision maker, you don’t have to choose a higher density neighborhood for yourself personally. But, its imperative that you understand the data behind why density actually adds value to a place and that good options are on the table for those who want it in your community.

Excellent presentation! Long ago, a wise mentor of mine once observed that to overcome our tendency toward sprawling suburban development, we must find a way to “make a virtue of density.” I liked that notion and often repeated it when working with local planning officials. Many nodded in passive agreement that it might be a good idea. But I realized they weren’t sold on it as they continued their support for low density development. I have come to understand that making a virtue of density implied, in their minds, some sort of sacrifice for the common good. But that’s just wrong for all the reasons set forth in this article. Where is the sacrifice in lower per-capita costs, more efficient use of public facilities and services and stronger, more vibrant communities?