Following our previous discussion of multi-generational housing opportunities, many readers have asked for specific guidance on how to actually transform an existing single-family home into a functional multi-unit property. The reality is that successful conversions require both creative design thinking and strategic navigation of local regulations. Here's your practical guide to making it happen.

Conversion Strategies That Work

The Basement Transformation

Converting a basement offers one of the most cost-effective paths to creating a second living unit. The key is ensuring adequate ceiling height, natural light, and proper egress. Adding a walk-out entrance transforms a basement from storage space into a genuine independent unit. Consider installing a kitchenette rather than a full kitchen—this often keeps you within zoning compliance while providing essential functionality.

A well-executed basement conversion might include a separate entrance through a side yard, two bedrooms, a full bathroom, a living area, and a compact kitchenette with a refrigerator, microwave, sink, and storage. The result feels like an apartment while technically remaining a "guest suite" in the eyes of many zoning codes.

The Garage Conversion Plus Addition

Attached garages present excellent conversion opportunities, especially when combined with a modest addition. The existing structure provides the foundation, while a small addition can accommodate a bathroom and separate entrance. The original garage space becomes a comfortable living area, and the addition handles the wet areas that require plumbing.

This approach works particularly well for families where the senior generation prefers single-level living. The converted space feels entirely separate while remaining connected to the main house.

The In-Law Suite Addition

For properties with adequate lot space, a modest addition can create a perfect multi-generational solution. A 600-800 square foot addition with its own entrance can include a bedroom, bathroom, living area, and kitchenette. The key is designing the addition to complement the existing home's architecture while creating clear separation.

The Upper-Level Independence

Homes with finished second floors can often accommodate conversion with minimal structural work. Installing a separate entrance—perhaps through an existing side door or a new external staircase—creates independence while maintaining the single-family appearance. A small kitchenette addition upstairs, combined with a private entrance, transforms the space entirely.

The Split-Level Solution

Split-level homes naturally lend themselves to multi-generational conversion. The lower level often already has a separate entrance and can be enhanced with a kitchenette and bathroom upgrades. The natural separation between levels provides privacy while maintaining connection.

Plan Sets

The good news is that many designers have been thinking about multi-generational housing for a long time. There are a lot of ready-made plan sets for this type of housing that you can learn from and be inspired by. This website offers 193 different house plans that include multi-generational design options.

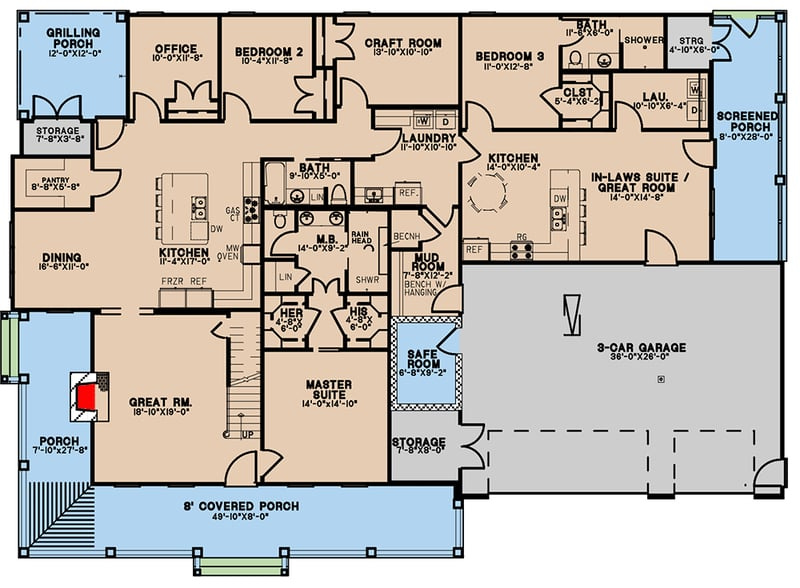

Floor plan for a single family home with an in-law suite behind the garage.

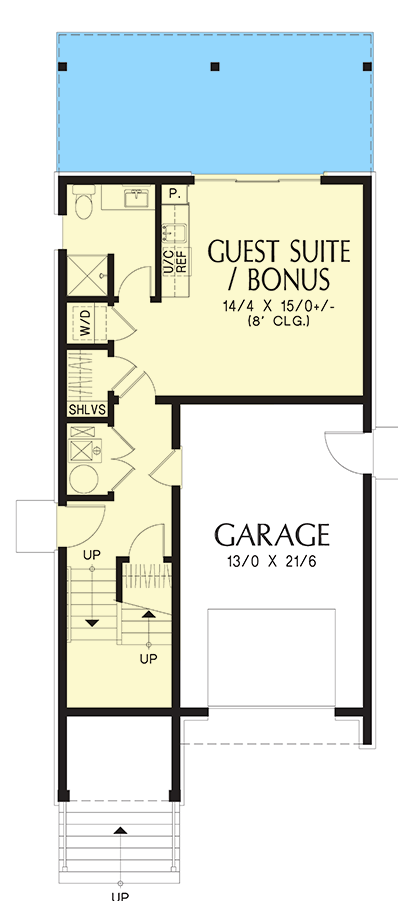

A 2 1/2 story home with a guest suite on the lower level.

The Kitchenette Strategy: Smart Zoning Navigation

Here's where practical wisdom meets regulatory reality: the difference between a "kitchen" and a "kitchenette" often determines whether your project triggers multi-unit zoning restrictions. A full kitchen typically includes a full-size range, oven, or similar hard-wired cooking facilities. A kitchenette, however, might feature:

A compact refrigerator (apartment-size or counter-depth)

A microwave or convection microwave instead of a full oven

Limited counter space (under 20 linear feet)

No dishwasher or a compact countertop model

This distinction allows you to create a functional space while maintaining the legal status of a "guest suite" rather than a second dwelling unit. The residents can prepare meals and live independently, but the space doesn't technically qualify as a separate kitchen under many zoning codes.

Similarly, consider these terminology strategies:

Call it a "guest suite" or "in-law apartment" rather than a "second unit"

Reference "auxiliary living space" in permit applications

Describe kitchenettes as "refreshment areas" or "coffee stations"

Frame separate entrances as "convenient access" rather than "independent entrances"

Working With Code Limitations Creatively

Successful multi-generational housing often requires creative interpretation of existing codes rather than wholesale zoning changes. Consider these approaches:

Parking Solutions: If codes require two parking spaces per unit, but you're creating a "guest suite," you might only need one additional space. A widened driveway or a parking pad tucked beside the house often satisfies this requirement without major expense.

Utility Connections: While separate utility meters might trigger multi-unit classifications, sub-metering through the main service often remains compliant. This allows for separate billing while maintaining single-unit status.

Setback Workarounds: If additions would violate setback requirements, consider whether covered walkways, pergolas, or other structures that don't qualify as "enclosed space" might provide weather protection without triggering setback rules.

Occupancy Flexibility: Many codes limit "unrelated" occupants but don't restrict family members. Multi-generational housing naturally fits within family occupancy provisions.

A Word to Planning Officials: Focus on What Matters

Local planners and zoning administrators face an impossible task: perfect enforcement of complex codes written for idealized situations that rarely match real-world needs. Every day, in every community, dozens of property owners make modifications that technically violate some zoning provision. Someone builds a deck slightly too close to the property line. Another adds a bathroom in their basement. A third converts their garage to a workshop.

The question isn't whether your community has zoning violations—it's which ones actually matter.

Multi-generational housing modifications that create functional independence while maintaining neighborhood character represent exactly the kind of beneficial use that codes should facilitate, not frustrate. When a family converts their basement into a comfortable living space for an aging parent, they're solving a real problem without harming anyone.

Smart enforcement focuses on issues that genuinely impact community welfare: safety concerns, genuine nuisances, or developments that fundamentally alter neighborhood character. A grandmother living in a converted garage with its own entrance doesn't threaten neighborhood stability—it enhances it.

Consider adopting an enforcement philosophy that asks: "Is this actually causing problems for neighbors or the community?" If the answer is no, perhaps that enforcement action isn't the best use of limited municipal resources. Your community likely faces bigger challenges than whether someone's kitchenette has a full-size stove or just a cooktop.

Practical enforcement means acknowledging that families will find ways to live together regardless of what your code says. Better to channel that impulse toward safe, well-designed solutions than to push families toward unsafe workarounds or force them to live apart when they'd prefer to be together.

Making It Official: When to Seek Permits

While creative interpretation helps navigate zoning challenges, certain modifications require proper permits for safety and legal protection:

Always Permit: Electrical work, plumbing additions, structural modifications, and new construction. These changes affect safety and property value.

Consider Permitting: Interior renovations that don't involve structural, electrical, or plumbing changes might not require permits in some jurisdictions, but permitting provides legal protection and ensures proper documentation.

Document Everything: Even unpermitted work should be professionally done and documented. Future buyers and insurance companies will want evidence of proper installation.

Building Support One Conversation at a Time

Successful multi-generational housing often depends on community relationships as much as regulatory compliance. Talk to neighbors about your plans. Most people understand the desire to care for aging parents or help adult children get established. When neighbors see the human story behind the renovation, they're less likely to complain about technical zoning violations.

Similarly, building relationships with local planning staff can pay dividends. Most planners entered their profession to help communities thrive. When you frame your project as a solution to real family needs rather than an attempt to circumvent regulations, you're more likely to find collaborative rather than adversarial responses.

The Bottom Line

Converting existing homes for multi-generational living requires balancing practical needs with regulatory realities. Success comes from understanding that the goal isn't perfect code compliance—it's creating safe, functional living arrangements that serve real families while respecting community standards.

The families choosing multi-generational living aren't trying to exploit loopholes or harm their neighborhoods. They're trying to care for aging parents, help young adults build financial stability, and maintain family connections in an increasingly disconnected world. Communities that support these efforts through reasonable enforcement and flexible interpretation of existing codes will find themselves with stronger families, more stable neighborhoods, and more efficient use of existing housing stock.

The alternative—rigid enforcement of codes written for different times and different family structures—pushes families apart and wastes opportunities to address real housing needs with practical solutions. In a time of housing challenges, that's a luxury most communities can't afford.

Thanks for this! It’s helpful to my practice which focuses on creative zoning interpretation and using functional family law to allow small-scale communal living and multigenerational living arrangements. I’ll be taking a closer look at guest suite and kitchenette laws after reading this.

While it is true that few object to a "granny flat" or other accessory dwelling intended for family members, objections often center around probable future uses. For example, I once heard a Planning Commissioner ask during a discussion on ADUs, "What happens to that granny flat when granny eventually passes?" Are there creative solutions to this issue short of simply amending the zoning ordinance to allow two-family units?