How to Make Housing Affordable: Beyond Band-Aids to Real Solutions

Part 1 of a series on creating truly affordable housing

The Heroes Working Against Impossible Odds

Every community has them—nonprofit housing heroes working 60-hour weeks for half the pay they could earn elsewhere. They're raising millions from donors, navigating complex public agencies, and building deep relationships with the families they serve. They know every story: the single mom who dreams of homeownership, the family facing eviction, the worker commuting two hours because they can't afford to live where they work.

These leaders are doing extraordinary work. They're also drowning.

The Triage Trap

Here's the problem: our housing heroes spend so much time in crisis mode—housing one family, creating one homeownership opportunity, preventing one eviction—that they don’t have the time to pull out of the daily grind and use their expertise to fix the broken system creating all these crises in the first place.

We're treating symptoms while the disease spreads.

The Real Problem: We've Outlawed Housing Choice

The uncomfortable truth is that local governments have systematically limited the housing choices individuals can make. Want your kids in the best schools? You'll need to afford the most expensive neighborhoods. Need to downsize after retirement or upsize for a growing family? Chances are you'll have to leave your community entirely, abandoning the neighbors and friendships you've built over years in order to select a different size or type of housing than the one you live in today.

This isn't just unfortunate—it's a manufactured crisis.

Why Good Intentions Aren't Enough

Here's the mathematical reality: For as long as there's a housing shortage, there will be an affordability crisis. Period.

No amount of heroic nonprofit intervention can solve housing affordability when the fundamental problem is scarcity. The less successful we are at improving overall housing supply, the more we'll depend on philanthropy and charity. But these heroes can't do it all forever, and they can't help everyone when the problem keeps growing.

Consider this: when people working 40-70 hours a week can't afford to live near where they work, that's not a charity problem—that's a systems problem requiring political will and better policy.

The Three Paths Forward

Path 1: The Subsidy Route

Continue funding nonprofits and subsidizing housing for those who need it most. This is essential but insufficient—it's treating symptoms, not causes.

Path 2: Remove Barriers for Big Developers

Clear regulatory obstacles and let traditional developers build more. This helps, but has a fatal flaw: current developers depend on scarcity for high returns. They'll only build until profits drop, never reaching true abundance. We need their investments, but their investments are not enough on their own.

Path 3: The Abundance Approach (The Real Solution)

Create systems that support both large-scale developers AND a "small army" of small-scale builders, developers and landlords who want to work on and with their own communities to create housing options that meet the needs of their neighbors.

Meet the Small-Scale Developer Revolution

The game-changer isn't another mega-developer—it's the school teacher who fixes houses during summer break, the firefighter who renovates on off-days, or the retired accountant who loves transforming abandoned lots into townhomes.

What makes them different:

They're often satisfied with smaller returns than big developers who are dependent on private equity chasing double digit returns

They hold properties for generations, not quick exits

They invest in entire neighborhoods, not just individual buildings

They build generational wealth within communities

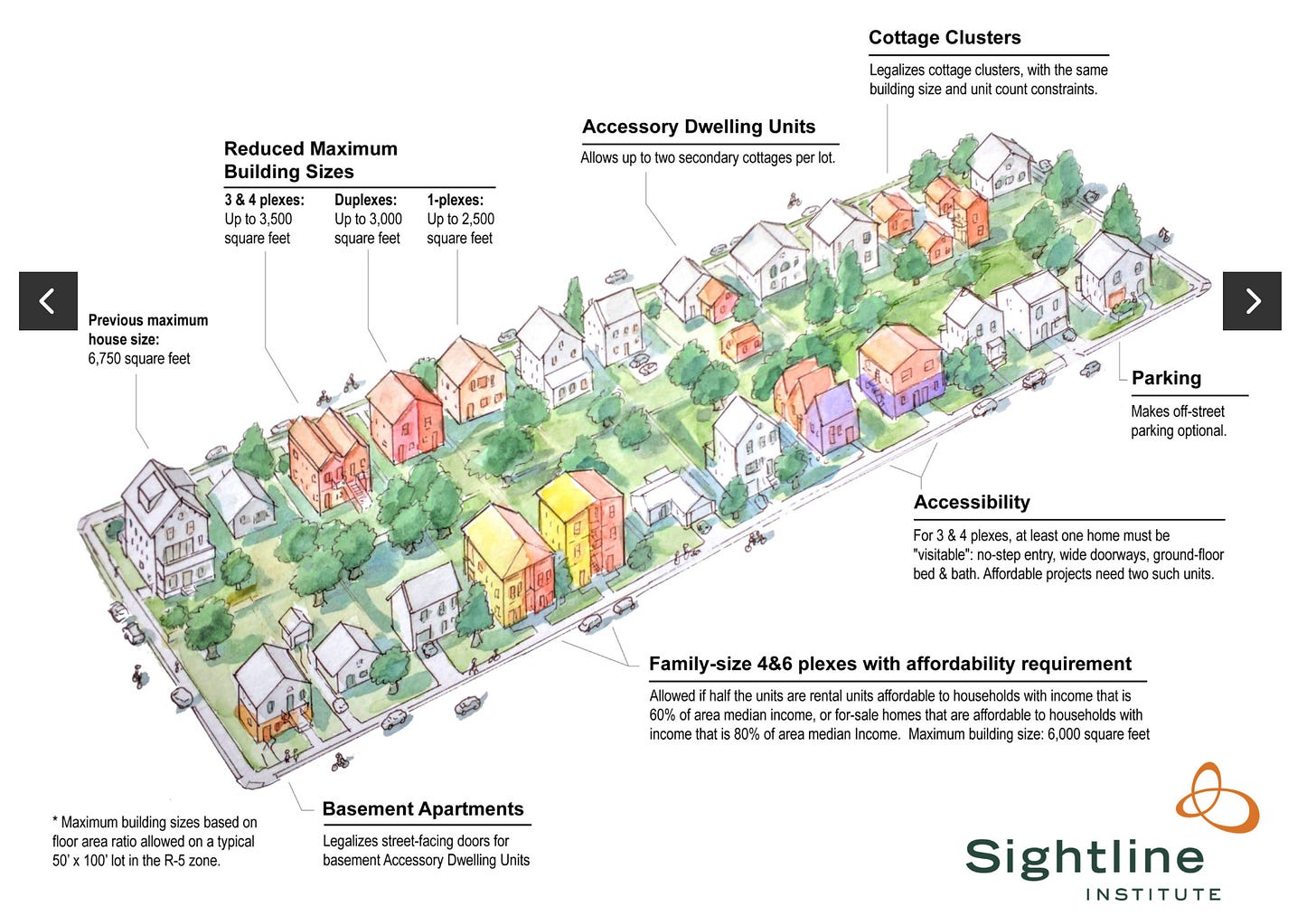

The catch: They can only exist where small-scale development is actually legal and feasible.

The Permission Problem

Right now, in most communities, these small-scale developers are essentially illegal. Converting a single-family home into a duplex? Bureaucratic nightmare. Adding a backyard ADU? Good luck with the permits. Building missing middle housing? Forget about it.

For the abundance approach to work, these opportunities need to be possible across entire regions—not just in a handful of "special" neighborhoods.

The Complex Reality of Current "Solutions"

Want to see how broken our current system is? I just read about an Atlanta development being praised as an affordable housing “breakthrough”. When someone asked about the financing, here's what it took:

Eight different funding sources

Four separate loans (each with different underwriting standards)

Four different grants (each with different compliance requirements)

Imagine the time and energy that a developer will spend on loan compliance and grant reporting—time that could be spent building more housing for families who need it.

What's Coming Next

This is just the beginning. In the upcoming parts of this series, we'll dive into:

Specific tools to make housing immediately more affordable

Data showing how housing supply affects market-wide affordability

Practical strategies for communities ready to embrace abundance

Financial innovations that could reshape how we fund housing

The Bottom Line

We need our nonprofit heroes, and we always will. Some individuals will always need community support due to disabilities or insurmountable circumstances. But when working families can't afford basic housing, we've failed at a systems level.

The long term path forward isn't more charity—it's abundance. And abundance requires not just removing barriers for big developers, but creating space for the small-scale builders who could transform our communities, one project at a time.

The question isn't whether we can afford to pursue housing abundance. The question is whether we can afford not to.

What barriers to small-scale development do you see in your community? Share your thoughts and experiences as we explore practical solutions in the coming weeks.

I need to push back on the narrative about nonprofit housing heroes. In your effort to champion systems reform, you draw a line that doesn't need to exist—suggesting that nonprofit housing workers are exhausted and stuck in triage mode. You say we're too tired and busy with our charitable helping professions to tackle root causes.

That's not the full story. The nonprofit housing leaders I know are not just helping one person at a time or building and preserving affordable housing one house at a time. We are—and have been—reshaping how housing gets done from the grassroots to the system level through advocacy, principled action, and innovation. We're not sidelined by symptom management.

Nonprofit Housing Leaders Are Trusted Advocates for System Change

Because nonprofits are "community-owned," we must consistently refine and renegotiate our respective cases for support with a diverse set of stakeholders. While that can be exhausting, it also serves as a means of educating the broader civil society and policymakers about housing needs and barriers to development in our communities. Public awareness and feedback is where good policy change begins.

In Grand Rapids, for example, nonprofit developers were first to respond to concerns from grassroots neighborhood leaders. We began advocating for zoning reforms in 2018, ahead of the city's Housing NOW! legislation and years before other groups like the Chamber got involved in zoning reform work.

Nonprofit Housing Leaders Build for Marginalized People, Not Financial Margins

Your post argues that the answer is abundance—I agree, but who gets to it first? Less-regulated supply doesn't automatically lead to fairness in housing. You named it in your article: big developers depend on scarcity for high returns.

Even if our communities solve the problems created by zoning constraints, inflated material and labor costs, high interest rates, and investors' demands for good ROI force big developers to build housing for the "high-end" of the market first. They assume that the benefits of added supply will trickle down to those with fewer means, passively addressing the needs of those with the most of them.

Nonprofit leaders don't build for speculation first or prioritize investor ROI. We build with a passion for sustainability and stewardship. We intentionally leverage as many resources as possible to build for those in the most need first. We need intentional, inclusive housing development—grounded in community voice and aimed at uplifting those most at risk of being pushed out.

Successful big developers, and even the small army of small-scale builders, are averse to the risk that "risky tenants" might represent to their bottom line.

Nonprofit Housing Leaders Do More With Less and Create New Approaches

Nonprofit leaders aren't just building one house at a time with existing public tools like LIHTC and HUD programs. We leverage those tools to do so much more. We build to scale with an emphasis on beauty and positive neighborhood impact. We take those limited public dollars and match them with sweat equity, volunteerism, and donated funds. Further, the fees we earn from developing homes aren't siphoned off into private bank accounts—they're invested back into our social missions and often used to keep housing permanently affordable.

Our projects regularly juggle five to ten funding sources, each with their own compliance burdens. That's not because we're inefficient—it's because we're accountable. When a developer gets access to public dollars, whether through grants, LIHTC, or Brownfield TIF, there must be a means for ensuring they do what they say they will do. The outcome matters, and that requires some inherent inefficiency.

We are developing new housing where it's hardest to build. We are serving residents with the highest barriers to stability and creating ownership models that counteract decades of injustice. We do all that while staying rooted in the same neighborhoods where redlining once flourished and where displacement pressure has become a threat to legacy residents.

A False Trichotomy: Nonprofit Heroes, Big Developers, and the Small Army

Your readers might falsely conclude that nonprofit housing heroes do charity, unrestricted big developers are all altruistic capitalists, and small developers with friendly capital always become inclusive landlords. That assessment inaccurately stereotypes all these groups. Worse yet, it unfairly paints nonprofit leaders as thoughtless bleeding-heart do-gooders who bury their expertise and want to manage housing crises in perpetuity.

I'd encourage us to move beyond narratives that unfairly characterize nonprofit leaders. We're experienced advocates working toward reform while maintaining community accountability.

The housing crisis requires collaboration, and I believe we can better recognize the contributions of those who've been steadily working toward equitable solutions.

I’m glad you’re breaking this down into several posts - and talking about what it actually takes to get housing built on the ground. One of the things that has been driving me crazy about the Abundance debate is that people not involved with development or city planning are making glib statements about changing zoning…with little understanding of the challenges of doing that.

I do think that the population that is lowest income and most in need will not truly be served by a supply side approach. Large developers will not build if they don’t see a profit, and small developers, especially those just starting out, have a low tolerance for risk. Non profit developers have a place building at scale to serve the needs of the very low income, and that need is large and will not change until structural changes in society do - the education system, the criminal justice system, the orientation towards a service economy. Small scale developers can absolutely stitch a neighborhood back together and rebuild the social fabric we all are seeking. But, as the commenter before me states, all levels of development are needed.

I look forward to the rest of the posts in this series. It’s good to see more people on this platform translate the heady ideas of abundance into the real world.