The Hidden Architecture of America's Housing Crisis:

How Policy Failures Created Artificial Scarcity

America's housing shortage didn't emerge overnight. What we're experiencing today is the culmination of decades of policy decisions, regulatory barriers, and market distortions that have fundamentally altered how and where we build homes. Understanding the true nature of this crisis requires looking beyond simple supply and demand metrics to examine the structural forces that have constrained housing production and driven millions of Americans out of reach of homeownership.

The Perfect Storm: Three Converging Crises

Underproduction

Misplaced infrastructure investments

Local zoning restrictions

The roots of our current housing shortage can be traced to three interconnected problems that emerged and intensified over the past several decades. First, a dramatic underproduction of housing units stemming from the foreclosure crisis, increasingly restrictive zoning laws, and the withdrawal of infrastructure spending that had previously subsidized suburban expansion. Second, the failure to capitalize on urban revitalization opportunities despite clear market demand and ample available infrastructure, hampered by regulatory barriers and misaligned incentives. Third, the creation of artificial scarcity through zoning restrictions that prevent economically viable housing types from being built, driving up prices across the board.

These factors didn't operate in isolation. Instead, they created a feedback loop where each problem exacerbated the others, ultimately producing a housing market that serves neither developers nor residents effectively.

When the Music Stopped: The Foreclosure Crisis and Its Aftermath

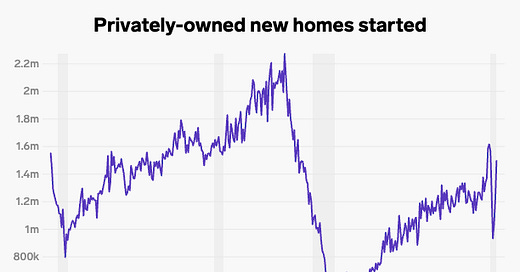

The 2008 foreclosure crisis marked a watershed moment in American housing production. In the aftermath of the financial collapse, homebuilding activity plummeted and never fully recovered to pre-crisis levels. Between 2008 and 2012, housing starts fell by more than 75%, and while construction has gradually increased since then, production remains well below historical norms relative to population growth and household formation.

After 20 years of underproduction, we’re still producing only half as many new homes each year compared to the early 2000s, despite national population growth of more than 50 million people.

This underproduction wasn't merely a temporary response to market conditions. The crisis fundamentally altered the financing landscape for residential development, making it more difficult and expensive for builders to access capital. Stricter lending standards, increased regulatory oversight, and higher construction costs created additional barriers to housing production that persist today.

Perhaps more significantly, the crisis coincided with a broader retreat from the infrastructure investments that had made previous waves of suburban development financially viable. For decades, federal and state spending on highways, water systems, and other infrastructure had effectively subsidized suburban sprawl by socializing the costs of extending services to new developments. As this spending declined, the true cost of greenfield development became apparent, making it increasingly difficult to build affordable housing on the urban periphery.

The Urban Renaissance That Wasn't

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, demographic and cultural shifts had created significant pent-up demand for urban living. Young professionals, empty nesters, and others increasingly wanted to live in walkable neighborhoods with access to transit, cultural amenities, and job opportunities. Cities that had been written off during the suburban exodus of the 1960s, 70s and 80s were showing signs of renewed vitality.

Yet despite this clear market demand, urban revitalization faced enormous regulatory and practical barriers. Decades of disinvestment had left many urban areas with deteriorated infrastructure, environmental contamination, and fragmented land ownership patterns that made redevelopment complex and expensive. More fundamentally, zoning codes written during the height of suburban enthusiasm actively discouraged the types of mixed-use, medium-density development that urban markets demanded. In other words, rebuilding those original neighborhoods was illegal under local zoning.

Safety concerns and school quality issues further complicated urban investment decisions. Even as crime rates began declining in many cities during the 1990s, perceptions of urban danger remained widespread. Similarly, urban school districts that had suffered from decades of disinvestment struggled to attract middle-class families, creating a chicken-and-egg problem where the very people needed to support urban revitalization were reluctant to commit to urban living.

The result was a tragic mismatch between market demand and regulatory reality. Developers who wanted to build urban housing found themselves navigating a maze of zoning variances, environmental reviews, and community opposition processes that could add years to project timelines and millions to development costs. Many simply gave up, choosing instead to focus on the suburban single-family market where regulatory processes were more predictable, even if the options for building were all vanilla.

The Single-Family Trap

Unable to effectively serve urban markets, the housing industry doubled down on what it knew how to build: large single-family homes on suburban lots. This focus made sense from an individual developer's perspective, as suburban zoning codes were generally more permissive and straight forward for single-family construction, and the regulatory process was fairly streamlined.

However, this market focus created several problems. First, it failed to serve the growing number of households that preferred alternatives to traditional single-family homes. Second, it concentrated housing production in a market segment that was increasingly expensive to serve, as the costs of extending infrastructure to greenfield sites continued to rise.

Most importantly, the focus on single-family development meant that housing production became increasingly misaligned with actual demographic demand. While household formation rates suggested a need for smaller, more affordable housing units, the market was primarily producing larger, more expensive homes. This mismatch between what was being built and what was needed contributed to affordability problems across the housing spectrum.

Meanwhile, for all those who wanted to be in a more walkable environment, there weren’t enough new housing options to serve the growing market demand, so higher income-households began competing with the low and moderate income families that had occupied the older homes in urban neighborhoods for decades.

The Zoning Straightjacket

Perhaps the most pernicious factor in the housing shortage is the web of zoning restrictions that prevent economically viable housing types from being built in most American communities. In many areas, zoning codes written decades ago continue to mandate low-density, single-family development patterns that no longer make economic or environmental sense.

These restrictions operate as a form of artificial scarcity, limiting housing supply in areas where market demand would otherwise support higher-density development. The result is that many communities have zoning codes that effectively prohibit the types of housing that local residents actually want and need, from townhouses and small apartment buildings to accessory dwelling units and mixed-use developments.

Moreover, many local officials and their staff don’t understand all of the ways that local regulations are effectively eliminating housing choices from their communities. While the code may say that a particular type of housing is technically permitted, the gauntlet of site and building placement standards, FAR requirements, green space minimums, parking requirements, and a half dozen other factors actually make those housing choices entirely impractical and financially infeasible.

The economic impact of these restrictions extends far beyond individual communities. When zoning limits housing supply in high-demand areas, it forces households to compete for an artificially constrained stock of housing, driving up prices not just locally but regionally. Workers who can't afford to live near their jobs are forced to commute longer distances, contributing to traffic congestion and environmental problems while reducing their own quality of life.

The Price of Artificial Scarcity

The cumulative effect of these policy failures has been the creation of artificial scarcity in housing markets across the country. When regulations prevent the construction of housing types that would be economically viable and serve clear market demand, the result is predictable: too little housing gets built, and prices rise accordingly.

This artificial scarcity operates differently from natural scarcity. In a normal market, high prices would signal developers to increase production, eventually bringing supply and demand back into balance. But when zoning restrictions, regulatory barriers, and infrastructure constraints prevent this normal market response, high prices persist without triggering increased production.

The result is a housing market that serves almost no one well. Renters face rising costs and limited options. Potential homebuyers are priced out of markets where they want to live. Developers struggle with regulatory uncertainty and lengthy approval processes. Even existing homeowners, while benefiting from rising property values, often find themselves unable to downsize or relocate within their own communities due to limited housing options.

Breaking the Cycle

Addressing America's housing shortage will require confronting each of these underlying problems. This means reforming zoning codes to allow more diverse housing types, streamlining regulatory processes for urban redevelopment, and finding new ways to finance the infrastructure needed to support sustainable development patterns.

Most importantly, it requires recognizing that our housing shortage is not the result of natural market forces but of policy choices that have constrained supply and distorted demand. By understanding the true nature of this crisis, we can begin to develop solutions that address root causes rather than symptoms, creating a housing market that serves all Americans effectively.

For more background on these issues see the following resources:

“Reclaiming Your Community” - Majora Carter

“Fragile Neighborhoods” - Seth Kaplan

“Cities and the Creative Class” - Richard Florida

“The Public Wealth of Cities” - Detter-Folster

“Fixer Upper” - Jenny Scheutz

I agree with this piece… as far as it goes. But how does a piece about zoning reform and housing supply/demand so often avoid any mention of residential segregation as a factor that suppresses housing production? Some discourse does recognize that Euclidean zoning was deliberately designed as a tool of exclusion to replace overt Jim Crow racial zoning. But its almost never acknowledged that white avoidance of Black (and “too integrated”) neighborhoods artificially nullifies the availability of adequately zoned land and inflates prices/rents in predominantly white areas (“the”segregation premium”). Segregation suppresses demand and value in Black areas, often below the costs of construction. Hence investors wont invest, developers wont build, banks wont lend and buyers cant buy. Only subsidized housing with deep subsidies gets built invthose areas, further perpetuating segregation. This artificially engineered scarcity is not inevitable (“the true “social engineering”). But it will take intentional action beyond just zoning reform to reverse what has been engineered. At its root, the fair housing movement against exclusionary zoning recognized this truth. But its largely forgotten—-or glossed over by today’s zoning reformers.

The housing shortage has coincided directly with the rise of short-term rentals and private equity more than anything else. This argument that zoning is the cause is so far misplaced my developers, it’s becoming comical.

Portland, where we’ve had some of the most flexible and progressive zoning anywhere, and loads of missing middle housing before it was cool, has not kept up with demand. Hell, we even passed a regional affordable housing bond - happily. But places like sprawling Austin and other places in the south building predominantly single family homes? Prices going down!

Michigan has sprawled endlessly and haphazardly for half a century and has barely grown in population for the last 25 years. And this is a place where impact fees aren’t even legal - who needs ‘em when you can just build the perimeter of all the corn fields and throw in a septic?