The roots of the housing affordability crisis in America are complicated. There are at least two dozen ways that we will need reforms across the financial sector, regulatory standards, labor supply, material tariffs, and on and on. But there are also some easy solutions that are ripe for the picking, right now!

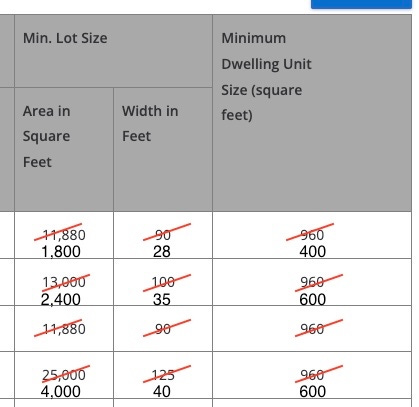

The simplest possible solution to create more abundant housing is to reduce minimum lot area, width, and unit size requirements.

If you're a local housing advocate, city planner looking to make a difference, or an employer trying to support your growing workforce, this is the low-hanging fruit you've been searching for.

1. Reduce Minimum Lot Sizes

All this requires is crossing out the existing number in your local zoning code and replacing it with one that makes sense in today's housing market. Don't hire a consultant. Don't spend six months studying the issue. Just replace the existing number with a more reasonable one.

This is literally as complicated as it has to be to change zoning. Its all in a Microsoft Word document. Just change the text, hold the requisite public hearing, and your community can open up an entirely new industry of small footprint homes. Be sure to comply with Public Act 110 of 2006 in Michigan.

Don't be afraid to allow lots that are smaller than you would personally choose. Remember that you don't pick out anyone else's wardrobe or choose what kind of car they drive. Why would you choose how large or how wide their property should be?

Some people genuinely want a one-bedroom cottage on a very small plot—perhaps a 700 square foot home on a 1,400 square foot lot. You might love this idea. You might not. But it's not about your personal preferences. It's about allowing people in your community to have real choices about how they want to live and how much they're willing to spend.

If your community has sewer and water available at the street, the minimum lot size should not be any larger than 4,000 square feet.

This does not prohibit people from having large lots and large houses. To the contrary, if someone has the desire and the means to own a large property and a large home, that’s fantastic. There is usually no such thing as a maximum lot size. But a thriving community builds for all income levels and housing sizes, not just the top tier consuming the most land. And we have to actually allow more naturally occurring affordable housing stock to get built.

2. Reduce the Minimum Lot Width

It makes no sense to allow a small cottage-sized property with a 100-foot width requirement. Consider reducing it to something like 30-40 feet.

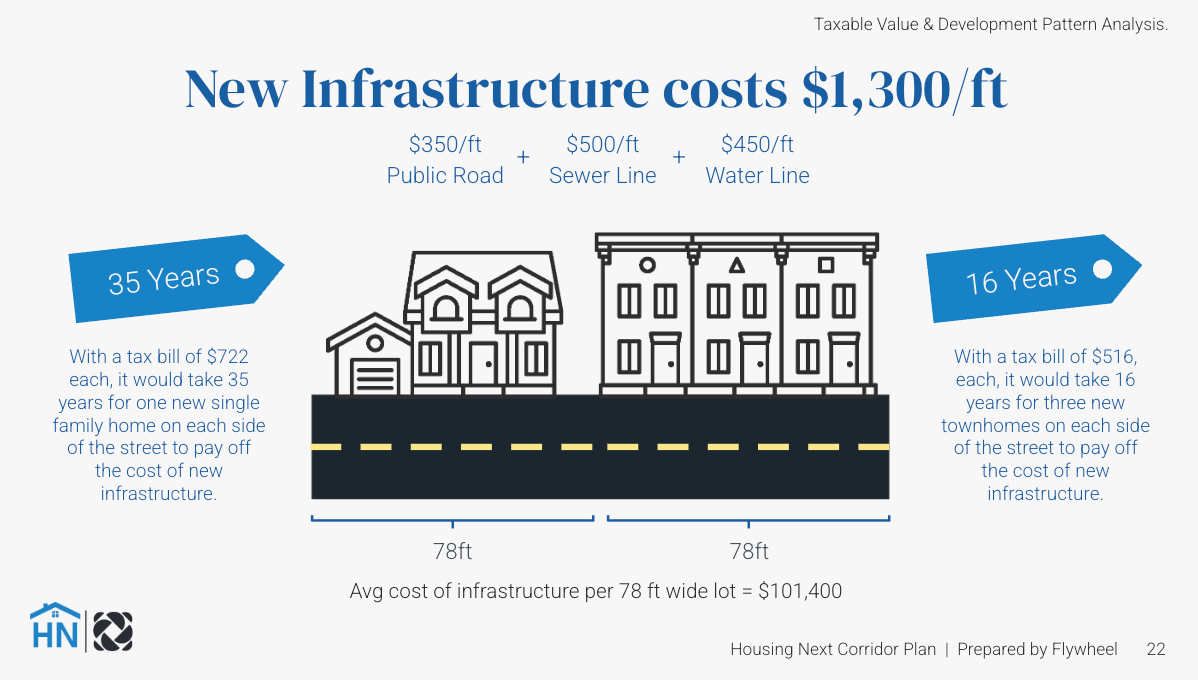

Again, if your community has sewer and water available at the street, you are wasting tax payer dollars by requiring excessively wide lots.

The cost to install, maintain, and replace 1,000 feet of sewer pipe, water pipe, and roadway is the same whether that infrastructure serves 10 homes or 25 homes. But if it serves 25 homes, it costs much less per household. This keeps usage rates lower and makes it easier to fund unexpected repairs over time.

This is why we build cities—to share the cost of services. But this only works when we're smart about our infrastructure investments. If we spread everything out, we lose all efficiencies and might as well put everyone back on individual septic systems and revert to dirt roads.

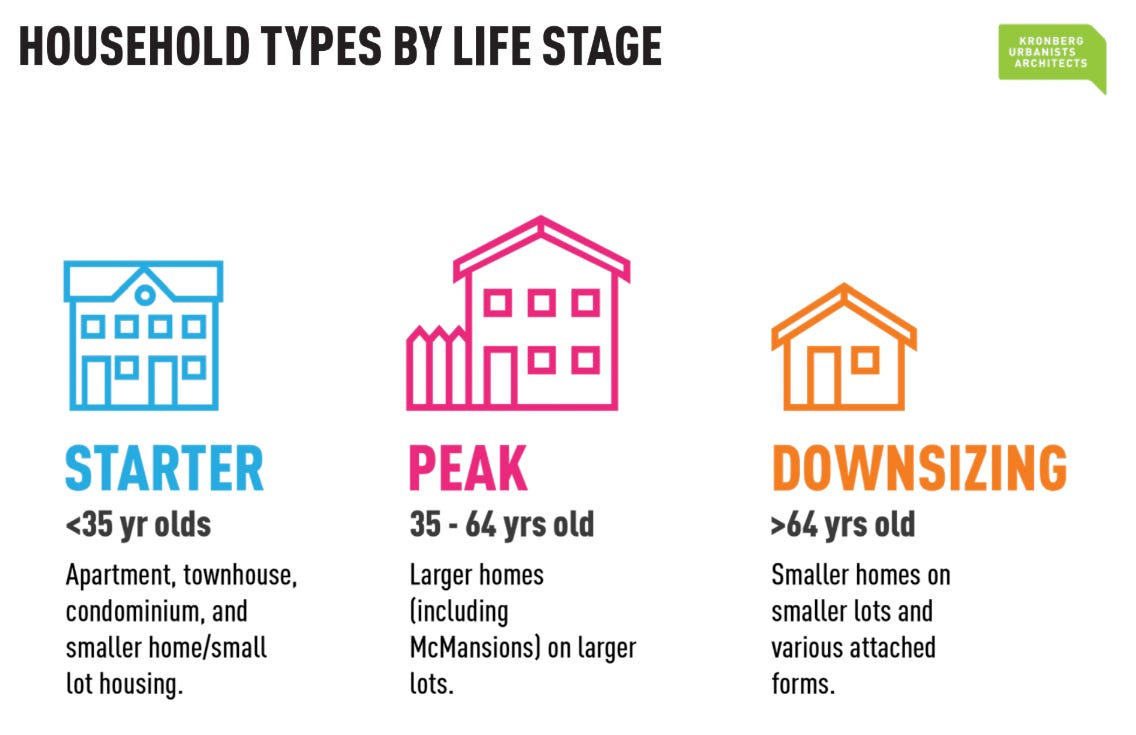

3. Reduce or Eliminate Minimum Dwelling Unit Size

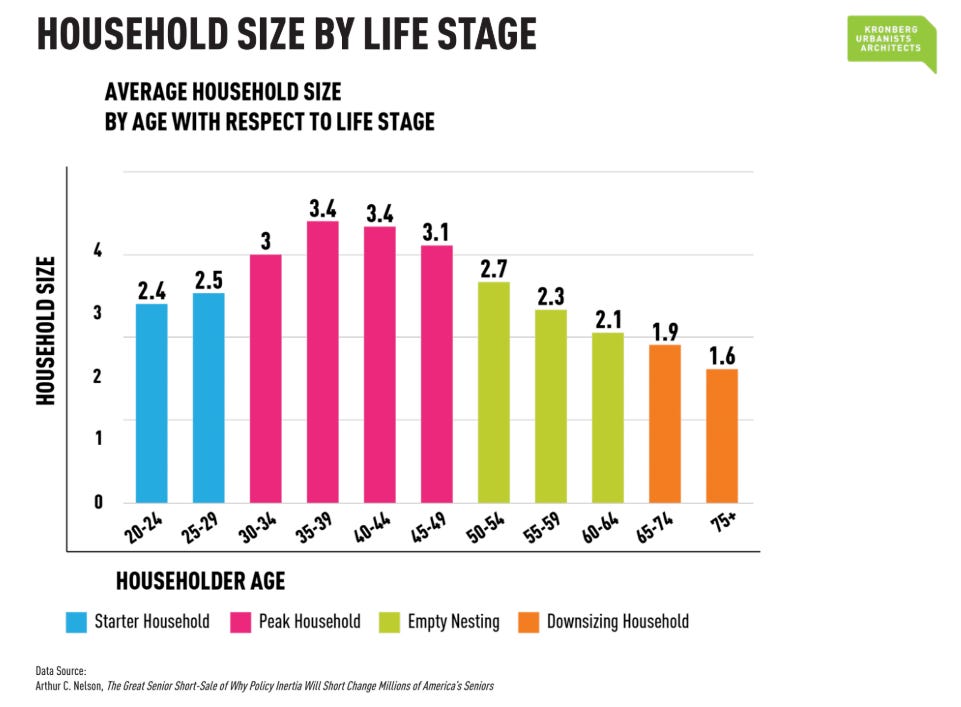

American building culture is quickly losing the art of the starter home and we’ve never really established an aptitude for the downsizer’s home. In the 1980s, nearly half of all new homes built were considered starter homes, priced for households earning around 80% of the area median income. Today, less than 10% of new homes fall into this category.

By 2030, demographers estimate that ⅕ of all households will be over the age of 65 in Michigan. And the share of downsizers will continue to grow.

Yet, many seniors are currently stuck in place. There are no options that make financial sense for them to move into. They have large homes with low interest rates and relatively little debt. But buying something that is half the size (or smaller) of their current home and twice as expensive feels… off. UNLESS it is paired with significant amenities. This would mean neighborhoods that are very close to friends and family and grocery stores and entertainment or volunteer options, and medical care. But we don’t allow these types of neighborhoods to be built in most places. So, instead, they are increasingly isolated in large single family homes on the periphery of their communities.

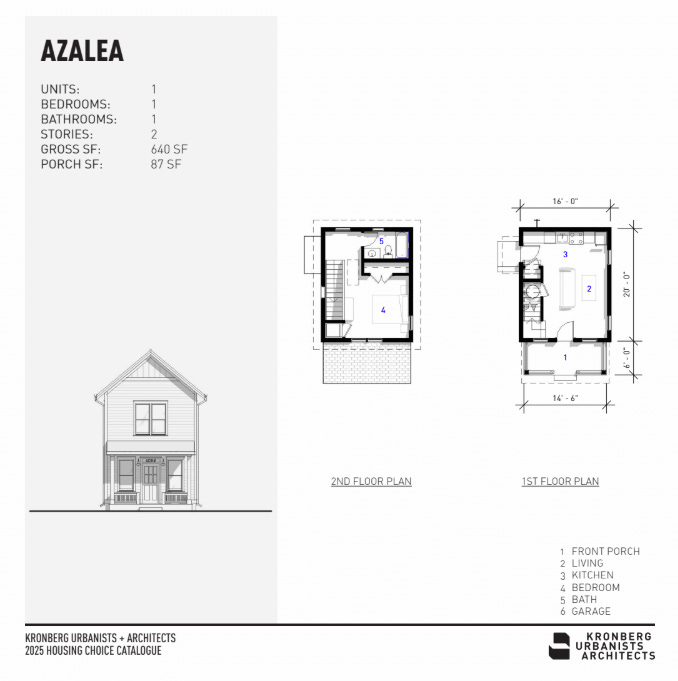

Generally, home construction is priced by the square foot. Kitchens and bathrooms cost more to build than bedrooms, so a 700 square foot cottage doesn't cost exactly one-third the price of a 2,100 square foot house. However, there should still be a 40-50% cost savings between the two.

Here’s an example of a 16’ x 20’ two-story home. It might not work well for 85% of households, but if this is a good solution for 15% of households in your community, it should probably be legal to build it. By the way, more than ¼ of all households are single adults without children at home.

If communities genuinely want to encourage homeownership amid a growing affordability crisis, why wouldn't we allow people to build homes that are reasonable for their family size and current life stage needs?

Of course, small homes don’t work for everyone. Families with several children might not fit comfortably in a 700 square foot cottage. But there are twice as many households composed of just one or two people as there are families with children at home. Even if only 10% of those smaller households would prefer a smaller home, where are their options?

Most local communities require minimum home sizes of 1,000 to 1,200 square feet. Again, this might be much smaller than what YOU personally want, but we shouldn’t be regulating our communities based on the personal preferences of a handful of individuals on the Planning Commission. Regulations should be designed to protect and promote public health, safety and welfare. Period. It's about allowing the whole community to have options that suit their needs.

The Hidden Truth Behind Large Lot Requirements

Minimum requirements of 12,000, 17,000, or even 24,000 square feet are common in local ordinances across the country, but they make absolutely no sense.

Ask yourself: What is actually achieved by requiring a 20,000 square foot lot instead of a 4,000 square foot piece to construct a home? How does the larger lot protect or promote public health, safety, or welfare?

When we spread more people out across the land, we are making a commitment to also spread our infrastructure out. This means building and maintaining more roads, installing more sewer and water pipe, and ultimately, building a lot more parking lots because nobody can get anywhere without their car.

Could we instead argue that making homeownership unreasonably expensive actually undermines public health, safety, and welfare?

Here's the uncomfortable truth: Many people believe they can control who moves into their neighborhood by regulating lot size. If land is more expensive to purchase, it “weeds out” people who don't earn enough to live nearby (I have actually heard this term from a local planning commissioner in our region). Some homeowners frame this differently—they claim they're protecting property values. But why would a smaller home on a smaller lot lower your property value?

When we examine property values in any neighborhood, smaller homes on smaller lots are indeed less valuable than large homes on large lots. However, on a per-square-foot basis, the smaller home is actually valued much higher.

For example, in a neighborhood of mostly 2,500 square foot homes on half-acre lots, the average property value might be around $400,000—about $160 per square foot. In that same neighborhood, a 900 square foot home of similar quality on a 5,000 square foot lot might be valued at around $280,000—about $311 per square foot. By creating the option for a small lot in a nice neighborhood, you're effectively offering a 30% discount on homeownership while maintaining access to the same schools, parks, and neighborhood amenities. Why would anyone be opposed to this?

The Character Myth

The other often cited rationale for requiring larger lot sizes is a desire to “protect rural character” or the “small town feel”. Everyone gets to have their own personal preferences when it comes to large lots or small lots, but is there anything about the image below that appears to undermine ‘rural character’ or ‘small town charm’? Do the smaller homes on smaller lots somehow conflict with the character of a small town?

Big lots often come with big roads and expensive infrastructure. All of the homes above are built on cul-de-sacs and the occupants are all likely to take the same route out of the neighborhood and onto the nearest arterial street, adding traffic and increasing the need for expensive traffic signals where left turns are becoming increasingly dangerous.

When homes are permitted on smaller and narrower lots, on a grid network of streets, we make it possible for neighbors to choose from a half dozen travel options in and out of the neighborhood. Walking and biking becomes a viable option. Or simply taking a secondary street with three right-hand turns to avoid the complicated left on the major arterial.

The Economic Impact of Minimum Lot Requirements

Land is priced by the square foot. Assuming two properties are fairly identical in location and attributes, the larger property will cost more.

Typically, homebuilders budget 10-20% for land costs. If an acre costs $100,000 and local government requires a half-acre lot, the builder has to spend $50,000 for the lot and will likely need to build a $300,000 house to justify that cost.

When local governments mandate minimum lot sizes, they're intervening in the market and moving away from free-market principles. They're establishing barriers that have little to do with the land's features and more to do with personal preferences and compartmentalizing families by income.

The same applies to minimum lot widths. Requirements of 70, 80, or 100 feet are arbitrary numbers. They're made-up figures that have been around long enough for us to believe they have meaning—but they don't. What they do accomplish is restricting housing supply and making housing more expensive. They also force more infrastructure costs on each property owner, whether they want the extra space or not.

A Call to Action

If you're serious about addressing housing affordability in your community, start with these three simple changes. Reduce lot area, lot width, and minimum home size requirements everywhere that has access to sewer and water. Schedule the public hearing, adopt the resolution, and be done with it.

Your community's outdated lot requirements were likely drafted when few people worried about maintaining aging infrastructure and when many erroneously believed larger lots would preserve rural character and maintain property values. We now know better.

Large lot sizes do inflate property values—but only by creating artificial scarcity in the market. Is that really the goal of your community's housing policy?

For more scholarly resources on this subject, please refer to the following:

Brookings Institute, Gentle Density

American Enterprise Institute, Light Touch Density

NYU Furman Center, The Case Against Restrictive Land Use and Zoning

This is a great article. I'm stealing these arguments for COS.

So, I live in a town that, where the infrastructure exists, did all three of those things (actually the minimum house size was eliminated as probably unlawful long before the other changes) 15 years ago. The result is that the cost of housing has nearly doubled. Attractive homes on small lots (7.5 units to the acre) in the walkable growth center sell for the same, ocassionally more, than older homes on large lots. We were first, but similar changes that came later in neighboring towns have had the same result.

Having been there, I think you are deceiving people by saying these are easy changes. Easy to cut-and-paste, sure, but maybe not as easy poltically? That's not my point, though. Just please explain the reality that the changes you propose have, at least in some places, actually caused the cost of housing to soar.