In American culture, real estate developers often wear the black hat. They're frequently cast as greedy profiteers bulldozing charming neighborhoods, destroying pristine landscapes, and gentrifying communities. This villainization has deep cultural roots but presents significant challenges to addressing our current housing crisis. For decades, we've assumed that the very people building more than 95% of the housing in our country are somehow the enemy.

By examining the history of this antagonism and reframing development as something we can all participate in, we can chart a path toward more vibrant and inclusive communities.

The Making of a Villain: Developers in American Culture

The American relationship with development has always been complex. In the nation's early years, westward expansion celebrated the "improvement" of land through development. Yet by the late 19th century, a countermovement emerged with conservationists like John Muir advocating for wilderness preservation. Muir wasn't opposed to all development, but rather to unchecked growth that threatened ecosystems and wild places—a concern that remains relevant today.

The post-WWII suburban boom represented a new era of expansion. Developers like William Levitt created mass-produced housing that addressed acute shortages but also created homogeneous neighborhoods that spread into farmlands and forests, enabled by the auto industry and massive federal highway spending.

These mid-century neighborhoods often excluded minorities through redlining and restrictive covenants, while urban renewal programs demolished diverse, working-class neighborhoods—often communities of color—to make way for highways and public housing. Many mistakes made during this period, both intentional and unintentional, still affect the American collective psyche today.

By the 1960s, Jane Jacobs was leading the charge against urban planning that prioritized cars and "slum clearance" over human-scale neighborhoods. The 1970s environmental movement further cemented anti-development sentiment, with landmark legislation creating new hurdles for future development.

Hollywood and popular media reinforced these narratives, regularly portraying developers as villains in films from "It's a Wonderful Life" (1946) to "Up" (2009). The cultural archetype became fixed: developers care about profit, not people or place.

The Power Paradox

America's villainization of developers has triggered a regulatory backlash with far-reaching consequences. Over several decades, communities nationwide have tightened local zoning codes, often restricting development to large single-family homes on expansive lots—a vestige of old patterns of segregation wrongly claimed to "preserve rural character."

This constraint hasn't stopped development—it has transformed it into something less accessible and less sustainable. The result is our current scarcity of starter homes and diverse housing options that were once standard in most American neighborhoods. The economic ladder of opportunity once embedded in homeownership has been pulled up behind the generations who benefited from more permissive building eras.

Meanwhile, mandatory land consumption has created neighborhoods that are increasingly car-dependent, socially isolated, and financially vulnerable compared to their pre-WWII counterparts. Ironically, in attempting to protect communities from the perceived threat of development, these regulations have fundamentally altered the inclusive, connected nature of American neighborhoods—replacing it with something more segregated, expensive, and financially problematic.

The Housing Crisis and Its Consequences

The consequences of decades of restricted development are now painfully evident. The United States faces a housing shortage estimated at millions of units, with the gap particularly severe in high-opportunity metro areas. This scarcity drives up prices, worsens inequality, limits economic mobility, and contributes to homelessness.

When we block new housing in existing neighborhoods, we're not preserving communities—we're pricing out lower-income residents, forcing longer commutes, and preventing new generations from accessing opportunity.

The Rise of Small-Scale Developers: Democratizing Development

One of the most promising aspects of common sense and incremental growth principles is how they can diversify not just what gets built, but who builds it. The prevailing narrative of the developer as a faceless corporation or out-of-town investor isn't just culturally harmful—it's a direct result of policies that have made development increasingly capital-intensive and complex.

The Capital Barrier

Today's predominant development patterns create significant barriers to entry. Developing large single-family subdivisions or high-rise apartment complexes requires massive upfront capital, sophisticated financing, and the ability to navigate complex regulatory processes. This process naturally favors large, established firms with access to institutional capital—often the very entities that communities view with the most suspicion.

The resulting concentration of development power reinforces the disconnect between developers and communities. When the only viable developers are those who can marshal millions in upfront investment, we shouldn't be surprised when they seem disconnected from neighborhood concerns or when local residents simply don’t understand the math that makes development work. Why would they? We haven’t made it accessible to most.

The Missing Middle Developer

Compact development patterns and incremental infill create opportunities for "missing middle developers"—local builders, property owners, and entrepreneurs who have intimate knowledge of community needs but lack access to massive capital reserves. Consider these development pathways that become viable under more flexible zoning:

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) & Backyard Cottages: Any homeowner can become a micro-developer by adding a small unit to their property, creating housing while generating rental income. The capital requirements are typically in the tens of thousands rather than millions.

Lot splits and duplexes: Local builders can purchase a single lot, split it, and build two homes or a duplex, making efficient use of existing infrastructure while keeping projects financially manageable.

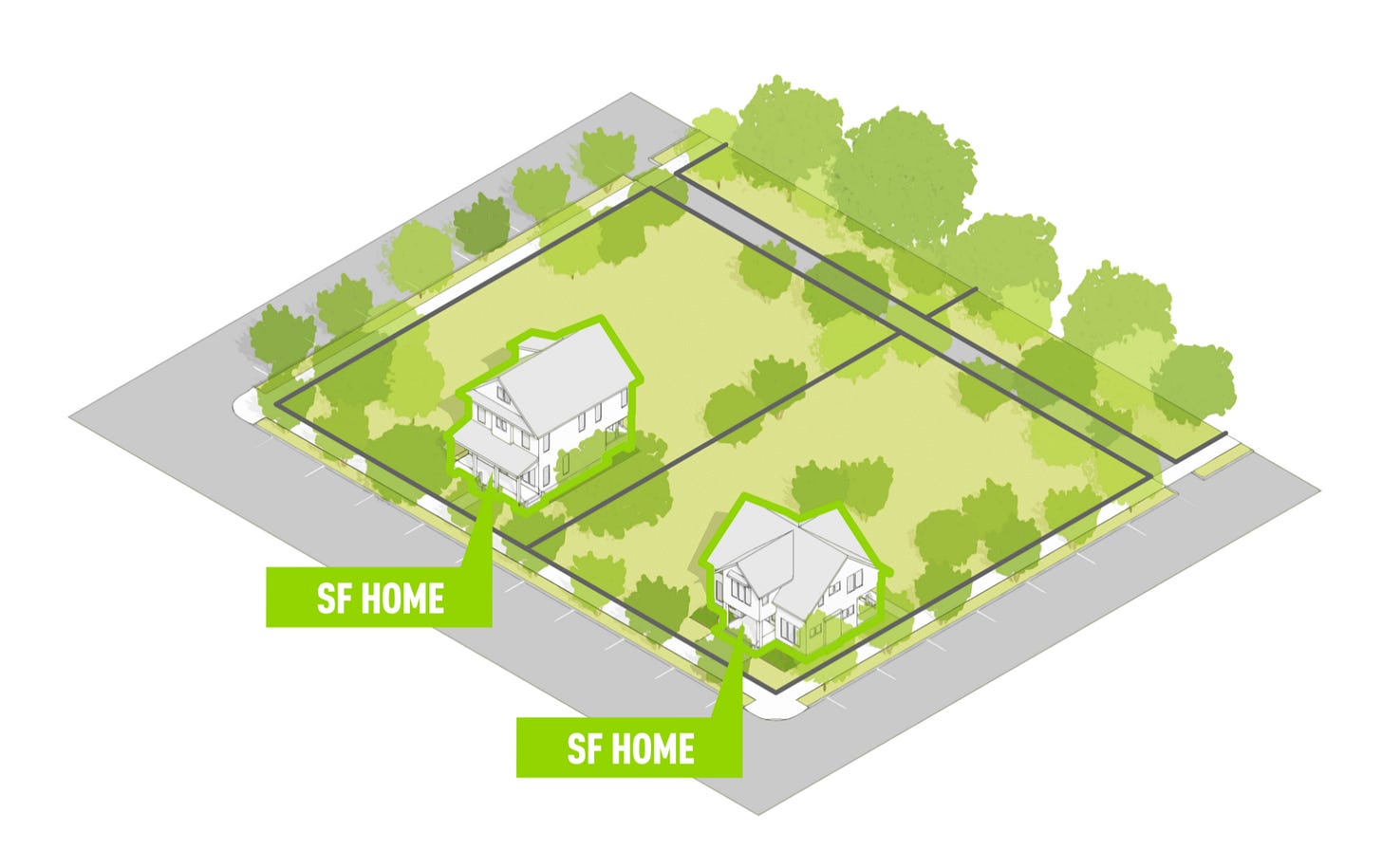

Two large single-family lots. Image credit: Kronberg Urbanists & Architects

Two lots subdivided (DADU = Detached Accessory Dwelling Unit). Image credit: Kronberg Urbanists & Architects

Small-scale apartment buildings: Four-to-eight-unit buildings, once common throughout American neighborhoods, can be built incrementally by local investors pooling resources. Ten neighbors can likely fund the construction of a 6-unit building at the end of their block without requiring a monumental investment from any one family.

A new four-unit building by Union Studio Architects.

Adaptive reuse: Local entrepreneurs can transform underutilized commercial properties into mixed-use developments with apartments above shops or offices.

Two commercial spaces and 10 one-bedroom apartments by Union Studio Architects.

Community Benefits of Local Development

When development becomes accessible to smaller, local entities, several benefits emerge:

Retained wealth: When locals develop property, profits remain in the community rather than flowing to distant investors or shareholders.

Responsive design: Local developers typically have a better understanding of neighborhood needs and preferences, leading to more contextually appropriate projects.

Incremental change: Small-scale development happens gradually, allowing communities to adapt rather than experiencing sudden transformations that spark resistance.

Diverse housing products: Small developers often create unique housing options that reflect local character, as opposed to the cookie-cutter approach that large developers may employ across multiple markets.

Face-to-face accountability: Unlike anonymous corporate entities, local developers are known community members who must face their neighbors at the grocery store or school pickup line—creating natural incentives for responsible development.

Collective knowledge: Sometimes, a large development can be very helpful to a neighborhood. Perhaps one that includes a ground floor grocery store or child care center. These can be too expensive for local neighbors to finance, but they can also create tremendous benefits to the broader community. When a few dozen neighbors understand how these projects are financed and the various trade-offs that have to be considered as it relates to the cost of parking, use of certain materials, the impact of building height on the budget, and simple floor plate efficiency, those neighbors can help the rest of the community recognize what is worth pushing back on and what is worth accepting to receive the community benefits of the investment.

Policy Shifts to Enable Small-Scale Development

Enabling this democratization of development requires specific policy approaches:

Simplified zoning: Clear, form-based standards that specify a building size and its relationship to the adjacent public spaces rather than micromanaging uses. This can make compliance more straightforward for small-scale developers and allow more opportunity for creativity and entrepreneurship. This means eliminating minimum lot sizes, floor area ratios, and limitations on dwelling units.

Graduated regulations: Applying less burdensome regulations to smaller projects acknowledges their reduced impact and lowers barriers to entry.

Technical assistance: Local governments can provide resources to help first-time developers navigate permitting and financing.

Access to capital: Community development financial institutions and local banks can create lending programs specifically for small-scale developers focusing on infill projects. These can be neighborhood-based or community-wide.

Streamlined permitting: By-right approval for projects meeting clear standards can reduce the time and uncertainty that disproportionately burden smaller developers.

From Opposition to Ownership

Perhaps most powerfully, when development becomes accessible to community members, the adversarial relationship between "developers" and "the community" begins to dissolve. Neighbors who might reflexively oppose any developer's proposal might view a local teacher's duplex project or a neighborhood family's small apartment building differently.

By enabling pathways for locals to participate in neighborhood evolution, we can transform development from something that happens to a community into something that happens by and for a community. This shift doesn't just produce better buildings—it repairs the social fabric damaged by decades of treating development as inherently suspect.

The small-scale developer model reconnects the act of building with the act of community stewardship, reminding us that development, at its best, isn't about extracting value but about creating places where people can flourish.

Public Investment: The Essential Companion to Development

For this vision to succeed, private development must be paired with strategic public investments:

Parks and green spaces: As our cities grow denser, accessible public parks become even more vital.

Complete streets: Roads designed for pedestrians, cyclists, and transit users—not just cars—make urban living pleasant and practical. We all want to give our children the freedom to explore their neighborhoods and interact with both adults and children in their community. But we have to make it safe for them to roam and wander just a little. Otherwise, it's no wonder they spend so much time staring at screens.

Community amenities: Schools, libraries, community centers, and small business districts create the "third places" where community bonds form. These places have to be embedded within neighborhoods and easy to get to - with or without a car.

Reframing the Narrative

Developers aren't inherently villains or heroes. They respond to the incentives and constraints we create through policy. By reforming zoning codes, streamlining permitting for projects that advance community goals, and investing in meaningful community amenities, we can align private development with public interest.

Many developers are already embracing this vision, building mixed-income, mixed-use, transit-oriented communities that exemplify common sense growth principles. These partnerships between developers, communities, and public agencies show what's possible when we move beyond simplistic villainization.

By recognizing the legitimate concerns that fueled anti-development sentiment while acknowledging the consequences of restricted housing production, we can forge a new approach that meets our urgent housing needs while building communities we can all take pride and ownership in.

The choice isn't between unbridled development and no development—it's about thoughtful, inclusive growth that serves both current and future generations.