Walk into any city council meeting, neighborhood association gathering, or community forum about housing, and you'll inevitably hear some variation of the phrase "Why don't they just..." followed by what seems like a perfectly reasonable suggestion. Why don't they just build more affordable housing? Why don't they just keep taxes low? Why don’t they put a grocery store there? Why don’t they just put in light rail? Why don't they just maintain our neighborhood character while solving the housing crisis?

These well-intentioned questions reveal a fundamental disconnect between what communities want and what's mathematically possible within our current systems. The problem isn't that city planners, developers, or elected officials lack creativity or compassion. The problem is that many of our collective expectations exist in contradiction to basic economic and fiscal realities.

The Impossible Trinity of Local Government

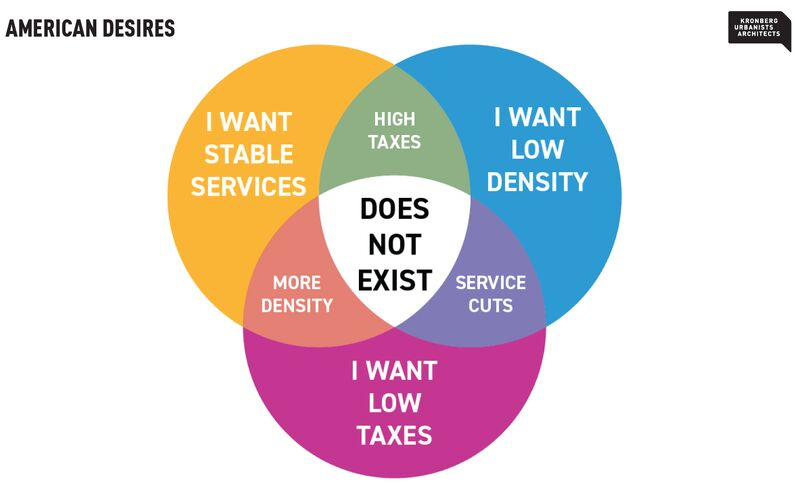

This Venn diagram has been around for a while, but Kronberg Urbanists and Architects recently made it a little easier to read. It perfectly encapsulates the issue: Low Taxes, High-Quality Services, and Low Density.

The harsh reality is that the intersection of all three circles is essentially empty space. You can have any two, but not all three.

This isn't a matter of political will or administrative efficiency—it's fundamental math. Cities and neighborhoods thrive financially through density because it allows the cost of infrastructure, services, and amenities to be distributed across more taxpayers per square mile. When you spread those same costs across fewer people in a low-density environment, the per-capita burden necessarily increases (or you fall off a fiscal cliff evenutally).

Consider the basic economics: a mile of water pipe, sewer line, or road costs roughly the same whether it serves 10 households or 100. The difference is whether those infrastructure costs are divided by 10 tax-paying units or 100. Emergency services, schools, libraries, parks, and public transit all follow similar mathematics. More density means more people contributing to the same pot of money that funds shared resources.

The following GIF is a bit long, but I’ve never seen a more complete and simple to understand explanation of this concept. It’s well worth watching, maybe twice.

Even though having more homes on the same amount of infrastructure is the KEY to making neighborhoods more economically viable, diverse, and affordable, density often gets framed as the enemy of quality of life. It's actually what makes quality of life financially sustainable. Those charming, walkable neighborhoods that everyone loves—from Brooklyn brownstones to Capitol Hill rowhouses—are dense by American suburban standards. Their density is precisely what makes them economically viable enough to support the local businesses, frequent transit, and community amenities that make them desirable.

This is where we have to have a caveat to say that suburban and rural communities are also really great places to live. About half of American families prefer these environments. We simply have to be honest about what is possible in the suburban or rural context. Generally, rural places don’t have a lot infrastructure or services and local residents are okay with that. Often times, they move to a rural place “to get away from the city”. And this is a fine choice.

Where I usually see discord begin to emerge is when people want to live in a low density environment, but they also really want sidewalks, and snow plowing, and trash service, and a great neighborhood library, and a top 10 public school district, AND they want no traffic, but everything within a five minute drive. These are the places that must either have REALLY high taxes, or they cannot exist simply due to financial constraints.

The Renter Reality

Here's where the math gets even more interesting: renters often contribute significantly more to local property tax revenue than homeowners, yet receive less political representation in community discussions and get characterized as “moochers” (or worse) in local town hall meetings. While homeowners typically benefit from homestead exemptions that cap their property tax increases and provide an annual reduction in property taxes, rental properties pay the full assessed value. These higher tax contributions from rental properties help subsidize the very services that homeowner-dominated neighborhood groups demand.

When communities resist rental housing or higher-density development, they're often rejecting the very thing that could help them maintain their desired service levels while keeping taxes manageable. The irony is striking: the people most likely to attend community meetings and oppose density are often the ones benefiting from tax policies that shift more of the burden to the renters they're trying to exclude.

The Affordability-Density Paradox

Perhaps nowhere is the "Why don't they just..." thinking more apparent than in public critiques of new developments. Community members regularly demand two things that are mathematically incompatible: less density and more affordability.

"Why don't they just build affordable housing instead of all these expensive condos?" is a common refrain. But here's the fundamental contradiction: affordability at scale requires density. When land costs are high—as they are in most desirable neighborhoods—the only way to make housing affordable is to spread that land cost across more units.

If the local lot area requirement for a single family home is 10,000 square feet, and a 10,000 sq ft lot costs $100,000, this is simply the baseline expense to build a home. Then, you still have to invest all of the money in the actual construction. Chances are very high that the end result will be $450,000 or greater for a single family home.

Whereas, if a community allows single family homes on 2,500 square foot lots, and a 10,000 square foot lot costs $100,000, now the land cost for each home is just $25,000. It’s an immediate cost reduction of $75,000 just by adjusting the text in a local policy. But even better, now I don’t have to build an oversized house to justify the high land costs. Instead, I can build something modest and will likely have a home priced at or below $300,000. Not because it required a subsidy, but simply because the community allowed for the incremental increase in density.

The resistance to density in the name of "neighborhood character" directly undermines the goal of affordability. You can have a neighborhood of exclusively single-family homes on large lots, or you can have housing that's accessible to teachers, firefighters, and young families. In high-cost areas, you increasingly can't have both.

This creates a particularly cruel dynamic where existing homeowners, who often purchased their homes when prices were lower, resist the very changes that would allow others to achieve similar homeownership opportunities. The "I got mine" mentality becomes encoded in zoning laws and community opposition to density.

The Infrastructure Reality Check

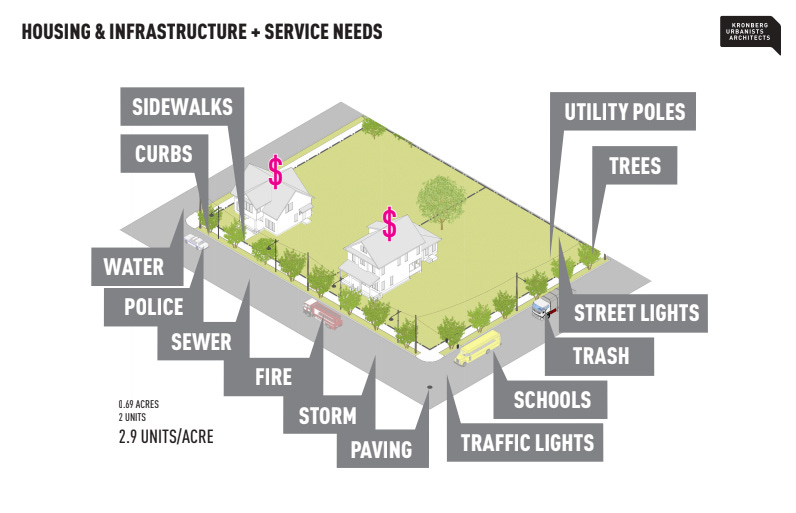

Behind every "Why don't they just..." question about municipal services lies an assumption that infrastructure and services can be provided efficiently at any density. This assumption doesn't hold up to scrutiny.

Low-density suburbs require the same basic infrastructure as dense neighborhoods—water, sewer, electricity, gas, internet, roads, snow removal, garbage collection, fire protection, police coverage—but with far fewer people to share the costs. The result is either higher per-capita costs, lower service levels, or unsustainable subsidies from other parts of the tax base.

If you didn’t watch the whole GIF above, this is a pretty solid example of our status quo environment in a lot of places.

Many suburban communities built during the post-war boom are now discovering this reality as their infrastructure reaches the end of its useful life. The cost to replace water mains, repave roads, and update sewer systems is the same whether there are 10 houses per mile of infrastructure or 50. Guess which scenario is more financially sustainable?

Moving Beyond "Why Don't They Just..."

Understanding these contradictions doesn't mean accepting the status quo or abandoning the goal of creating great communities. Instead, it means having more honest conversations about tradeoffs and more creative thinking about solutions.

The most successful communities are those that have learned to see density not as a threat to quality of life, but as a tool for enhancing it. Like any tool, density can be used well to create beautiful places where people of all ages thrive, or it can be used poorly and create places where a lot of people are concentrated but the environment is sterile or isolated from all of the amenities people need and want. The best communities have figured out how to channel growth in ways that strengthen rather than strain their community fabric.

The next time you hear someone ask "Why don't they just..." about housing and community development, the answer often lies in the fundamental math of municipal finance and the physics of urban economics. The question isn't why planners and developers don't do the obvious thing. The question is whether we're ready to align our expectations with economic reality—and whether we can envision forms of density that serve our communities rather than threaten them.

Great communities aren't built on wishful thinking. They're built on understanding how the pieces actually fit together, and making thoughtful choices about what we're willing to prioritize, fund, and change. The math may be unforgiving, but it's also clarifying. Once we understand the real constraints, we can start having more productive conversations about real solutions.

Good explanation. Two amendments:

First, the increase in the cost of services is not linear. This doesn't say that, but I think readers may read it into what is said. There are moments in the progression when adding density does require upgraded capital facilities and/or operating costs. For small places getting larger, a good example is the moment when the fire service switches from volunteer to full-time. And then when you have to buy a ladder truck. Density has added a substantial cost that wasn't there before. There are also moments when basic utilities and intersections have to be upgraded to accommodate more units/higher density. This doesn't change the message that cost per unit falls in the long run, but I think it is important to acknowledge that some substantial costs have to be absorbed along the way.

Second, how this impacts people is noticeably affected by both the state/local tax/fee structure and the quality of management. There's no general conclusion to draw about that. but I wonder if there is a correlation between mediocre management and NIMBYism.

Excellent overview of both the complexities and disconnects. Love the graphic! This is a visual business after all. Of course as it turns out, there may be more items to add to the venn diagram such as intergenerational mix, kind-of-like a village. Multi-generations have different living requirements but connect on many levels. (I keep thinking more university/college campuses should be building apartments for retirees. The advantage: continuous learning opportunities for retirees, intergenerational learning, on-going funding stream for funding-strapped post secondary education.)

We do need to keep this "Why don't they just ...?" conversation alive. Add in some more systems thinking.